Update: Breast cancer disparities in Black Americans

The American Association for Cancer Research (AACR) released a 2020 report about cancer disparities among racial and ethnic groups in the United States. In this review, we highlight findings on the burden of breast cancer in Black women. (posted 8/5/21)

Este artículo está disponible en español.

Contents

UPDATE AT A GLANCE

What is this update about?

This report is about gaps in breast cancer screening, rates and related deaths in Black women in the United States and factors that may contribute to these differences.

Why is this update important?

Unfortunately, some racial and ethnic groups in the US shoulder more of the cancer burden than others. This is referred to as cancer .

In its 2020 report, “Cancer Disparities Progress Report,” the AACR states the following:

“Cancer are adverse differences between certain population groups in cancer measures such as number of new cases, number of deaths, cancer-related health complications, survivorship and quality of life after cancer treatment, screening rates and at diagnosis.”

This review focuses on breast cancer in Black women in the United States. The report discussed:

- The difference in the rate of breast cancer among Black women compared to white women.

- The difference in the rate of death due to breast cancer among Black women compared to white women.

Disparities in the rate of breast cancer

Breast cancer is the most commonly diagnosed cancer among Black women in the US, with 33,840 new cases in 2019. While the breast cancer rate has been lower among Black women than white women for several decades, it has been rising steadily in recent years, and the rate is now similar among the two populations. For women under the age of 40, the breast cancer rate is higher among Black women than it is for any other racial or ethnic group. The rate of a biologically aggressive pattern called triple negative breast cancer is higher among Black compared to white women in all age groups.

Disparities in the rate of breast cancer-related deaths

Black women are 40 percent more likely to die from breast cancer compared to white women. This may reflect that:

- Black women are more likely to be diagnosed at a later of disease when treatment is less likely to be successful.

- Black women are more likely to be diagnosed with , an aggressive form of breast cancer.

- The impact of systemic racism on delivery of cancer care resulting in Black women being more likely to receive incomplete treatment for breast cancer.

What contributes to disparity in rate of breast cancer and related deaths?

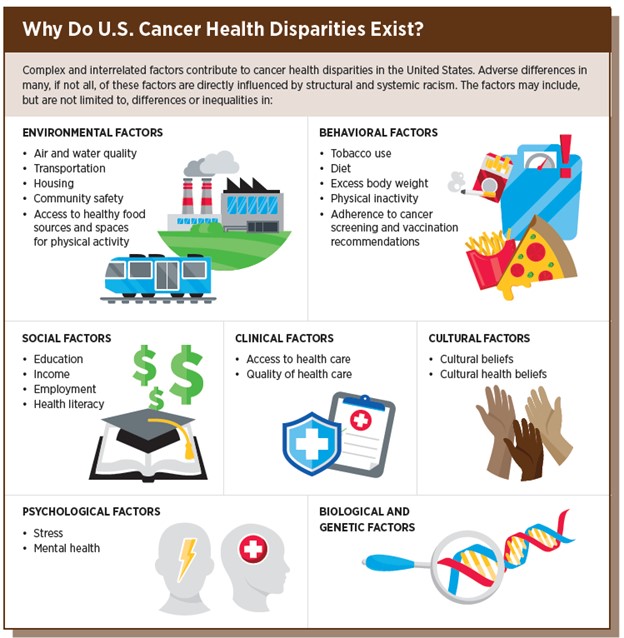

The following chart summarizes factors that contribute to cancer . It is important to note that most of these factors are the result of structural and systemic racism in our health care system.

CancerDisparitiesProgressReport.org [Internet]. Philadelphia: American Association for Cancer Research; ©2020 [posted August 5, 2021]. Available from http://www.CancerDisparitiesProgressReport.org/

Environmental Factors

Physical environment influences our health and our access to healthcare. For example, research shows that women who live in poverty in inner city urban neighborhoods are significantly more likely to be diagnosed with breast cancer. One study looked at the number of households receiving public assistance, the number of female-headed families, and the number of people who were Black, younger than age 18, unemployed, or those in a neighborhood who were living below the poverty line. Researchers found that Black women were more likely to live in neighborhoods where these measures were high. This was found to contribute to the disparity in stage at diagnosis and survival between Black and white women.

Other factors, such as air and water quality, are also linked to cancer. Outdoor air pollution causes lung and possibly other cancers. Importantly, Blacks and Hispanics have been reported to be exposed to higher levels of outdoor air pollution than whites. A study that looked at air pollution and other environmental hazards in California concluded that Blacks and Hispanics were more likely than whites to live near multiple environmental health hazards.

Behavioral Factors

Body Weight Physical Activity and Lifestyle

Fifteen types of cancer, including breast cancer, are directly linked to being overweight.

Significant disparities exist in rates of being overweight among different racial and ethnic populations. Obesity rates are highest among Black women and lowest among Asian men. Breast cancer and several other cancers that are known to have a higher burden among racial and ethnic minorities are associated with obesity.

Increased cancer risk is clearly associated with excess body weight, although the cause is not fully understood. Excess body weight can be due to a lack of physical activity. In the US, lack of physical activity accounts for about 4 percent of all breast cancers. In contrast, being physically active lowers the risk of nine types of cancer, including postmenopausal breast cancer.

Racial and ethnic disparities have been reported in people who are physically inactive, with Hispanics and Black Americans being less physically active than whites. These differences are not completely explained by economic status or the type of physical activity. One factor that may contribute to the breast cancer disparity between Black and white women is a condition called insulin resistance (sometimes called pre-diabetes). More Black women have insulin resistance than white women. One study found that insulin resistance might be a reason that Black women are more likely to die from breast cancer than white women. Read more about this study here.

Lactation/nursing has also been shown to reduce breast cancer risk. Lactation can reduce risk of all patterns of breast cancer, including triple negative disease.

Diet

In the US, almost 5 percent of all cancer cases and deaths among adults aged 30 and older are linked to eating an unwholesome diet. A poor diet lacks enough healthy foods, such as whole grains, fruits, nuts and seeds and an excess of unhealthy foods, such as sugar-sweetened drinks and high levels of red and processed meats. In the United States, overall diet quality improves with increased income level, which may contribute to cancer . Black Americans are more likely to live in neighborhoods that lack grocery stores and access to affordable fresh fruits/vegetables.

Incorporating more healthy salads into one’s diet can be an effective way to improve overall nutritional intake. Studies have shown that Blacks in the US have a lower intake of total vegetables and whole grains than whites. Diet quality for Black and white young adults has improved over the past two decades. However, while people from all income levels experienced an improvement in diet quality, the disparity between low- and high-income groups significantly increased.

Social factors

Social factors such as education, housing, neighborhood, income, employment and health literacy contribute to cancer . These factors are called “social determinants of health”.

Social determinants of health affect all individuals. Socioeconomic disadvantages, however, are disproportionately more common among racial and ethnic minority groups, thereby contributing significantly to racial and ethnic cancer . For example, in 2018, 21 percent of Blacks in the US lived below the federal poverty level compared with 8 percent of whites. In addition, 25 percent of Blacks have a bachelor’s degree or higher compared with 35 percent of all whites. Eliminating socioeconomic disparities is estimated to prevent 34 percent of cancer deaths among all US adults.

The socioeconomic status of individuals and neighborhoods can affect clinical, environmental, psychological, behavioral, and cultural factors that influence health, including access to healthy foods, spaces for physical activity, the Internet and transportation, as well as exposure to crime and violence. It is important to establish how much each factor contributes to racial and ethnic cancer so that disparities in education, housing, transportation, agriculture and environment can be addressed to achieve cancer health equity.

Access to information (or lack of it) also contributes to cancer in the US. Blacks in the US die from cancer more often than other racial and ethnic groups. Several studies have demonstrated that Black Americans are less likely to be offered comprehensive breast cancer screening and treatment options, including genetic testing and clinical trial participation. Having complete information about potential risk-reducing options allows people to make more informed choices and may impact their health outcomes. Understanding why differences exist in access to information can help to develop better ways to overcome this disparity.

Clinical factors

Insurance

Access to health insurance is a key factor in racial and ethnic cancer . For example, racial and ethnic minorities are more likely to be uninsured or to receive Medicaid compared to whites.

Black, Indigenous and Hispanic women are more than 30 percent more likely to be diagnosed with advanced breast cancer compared with white women. Nearly half of delayed diagnoses resulted from these women being uninsured or receiving Medicaid. While addressing health insurance status will not completely remove cancer , providing equitable insurance coverage can substantially reduce the burden of breast and other cancers for racial and ethnic minorities.

Breast cancer screening

Breast cancer screening rates for Black and white women in the U.S. are similar (see our XRAY review here). However, nearly twice as many Black women (9 percent) are diagnosed with advanced breast cancer compared to white women (5 percent). This contributes to more related deaths in Black women.

Factors that may contribute to this disparity in of breast cancer at diagnosis include longer intervals between screening, delayed follow-up of abnormal results, screening at lower-resourced and nonaccredited facilities and lower rates of follow-up care at a comprehensive care center. Differences in breast tumor biology also contribute, since Black women are more likely to be diagnosed with faster-growing more-aggressive breast cancers compared to white women.

Breast cancer treatment

Inequities in delivery of breast cancer treatment also contribute to disparities in outcome and quality of life.

Racial and ethnic minority women with breast cancer are less likely to receive radiation therapy, which can increase the risk of disease recurrence and death. For example, women with ductal carcinoma in situ () who live in rural areas were less likely to receive radiation therapy after breast surgery compared to who live in urban areas. Black and Hispanic women with breast cancer are more likely to experience delayed radiotherapy than white women. Black women with breast cancer are half as likely to be treated with radiation therapy as white women.

Black breast cancer patients undergoing mastectomy are significantly less likely to have breast reconstruction than white patients. Implicit bias and unconscious discriminatory practices by healthcare providers can also adversely affect a patient’s understanding of disease treatment.

Clinical trials

Clinical trials provide the opportunity to receive the newest available treatments. However, access to clinical trials is not equitable for all patients (also see XRAY review on importance of racial diversity in clinical trials here). Despite this knowledge, low participation in clinical trials and lack of diversity among participants are two of the most pressing challenges in clinical research.

Significant underrepresentation of racial and ethnic minorities in clinical trials is well documented and has been exceedingly low in key clinical trials leading to approval of immunotherapies. For example, Black women were underrepresented in a clinical trial that led to the approval of atezolizumab (Tecentriq) plus nab–paclitaxel (Abraxane) for women with advanced , even though this aggressive type of breast cancer disproportionally affects African American women.

To increase clinical trials enrollment and to ensure that participants more reflectively reflect the overall U.S. population, the NCI recently revised its eligibility criteria to expand access for previously excluded patients. Read more here. These new criteria encourage clinical trials to allow participation of people who have often been excluded, including those with secondary conditions like heart disease and diabetes and those with preexisting conditions such as brain metastases and prior and current cancer. Many Black Americans are disproportionately impacted by other health issues and may have been excluded.

Several studies have demonstrated that Black Americans have disproportionately low access to participating in clinical trials. Black Americans are less likely to receive cancer care in the large academic cancer facilities that are better able to afford the cost of clinical trials. Furthermore, research has also demonstrated that oncologists are less likely to offer clinical trials to their Black American patients compared to their White American patients.

Cultural factors

It is important to identify and understand cultural health beliefs and other cultural factors that influence behavior. Researchers are studying how culturally tailored strategies can be used to increase cancer screening awareness, access and uptake among different population groups.

Factors related to lifetime stress experiences

Growing evidence suggests that stress and the body’s response to stress may increase cancer rates, cancer deaths and poorer cancer survival rates. For example, women with breast cancer who report no traumatic stressful events in their lives are disease-free for twice as long as those who reported one or more traumatic stressful life events.

Stress can also contribute to cancer . Levels of emotional distress are significantly higher among Black cancer survivors compared with cancer survivors from other racial and ethnic groups. Stress may also contribute to the increased risk of certain aggressive cancers such as .

Social isolation and racial discrimination increase stress, which in turn is linked to increased cancer diagnoses and death. Even perceived discrimination has been linked to increased breast cancer among Black women. Social isolation and discrimination have also been linked to the of breast cancer at diagnosis.

The impact of stress on cancer risk and other aspects of health is being studied in an exciting and relatively new field of research related to the study of “allostatic load”. Research in this area is looking at how the cumulative effects of lifetime stress (including total lifetime experiences of discrimination) contributes to cancer outcome disparities. Allostatic load can influence cancer risk by disrupting our immune system and/or by affecting our .

Biologic and genetic factors

Researchers are interested in understanding the link between biological and genetic factors and cancer . Individuals with non-European ancestry however have been significantly under-represented in studies of genetic cancer risk. Ideally, these studies would include people of all groups in proportions that reflect the general US population and perhaps a higher percentage of participants for studies of cancers that disproportionately affect Black people.

Biological and genetic differences among populations may affect cancer . The CARRIERS study, which analyzed harmful mutations in a large group of women with breast cancer, found no differences in overall rates of inherited mutations among women of different races. However, the particular mutation in genes reflects the ancestry of the person. For example, numerous studies have uncovered differences in inherited mutations among white women (three common "founder" mutations that frequently appear in the Jewish population or a mutation called C61G that is common among women of Polish and Czech ancestry). Knowledge of common mutations among African American women of diverse ancestry has lagged but is increasingly recognized. For example, particular mutations in genes that are linked to breast cancer are common among Black women with roots in the Bahamas (linked here) while other mutations linked to breast cancer are more common among Black women with West African ancestry (linked here).

Several ongoing studies and initiatives, such as AACR Project Genomics Evidence Neoplasia Information Exchange (GENIE) and the NCI- funded African American Breast Cancer Epidemiology and Risk (AMBER) Consortium, are designed to address knowledge gaps about cancer biology in all populations.

Black women with a family history of cancer who may have a risk- that increases their risk face barriers to obtaining genetic screening (https://www.facingourrisk.org/XRAY/Gaps-info-breast-cancer-prevention-African-American-women). Black women experienced greater burdens in obtaining information at each step of the genetic screening process, were less frequently referred to a specialist or offered specific risk management information and were more likely to rely on primary care providers for all of their breast cancer information than white women.

Compared to white women, 50 percent fewer Black women with breast cancer have genetic testing (read our XRAY review here); the rate of surgeon referral for genetic testing seems to most affect this. These gaps in access and information limit decision-making about breast cancer care.

Everyone benefits by closing the cancer disparities gap

Reducing cancer would benefit everyone: a significant number of cancer related- deaths among all US adults could be prevented if socioeconomic disparities were eliminated. Read more here.

Eliminating among racial and ethnic minorities from 2003 to 2006 would have reduced direct medical costs by $230 billion and indirect costs associated with illness and premature death over $1 trillion dollars.

Conclusion

Researchers are making tremendous progress toward improved detection and treatment of cancer, including breast cancer. However, the stark reality is that these advances do not benefit everyone equally. The impact of systemic racism throughout the healthcare system creates an undue burden of cancer and cancer-related deaths among Blacks compared to whites. Eliminating systemic racism and its impact on the burden of cancer is one of the most immediate public health challenges in the US. Doing so would greatly improve cancer outcomes.

What does this mean for me?

If you are a Black woman in the US, your risk of breast cancer, especially more aggressive breast cancer, and breast cancer at young ages, may be higher than other people’s risk. This means that screening for early detection of disease and being aware of breast cancer danger signs is especially important among Black women.

Routine screening is essential, but overall breast health awareness means that you should promptly report any new breast symptoms to your physician, regardless of when your most recent was performed and regardless of your age. are not perfect and some cancers will be invisible on these breast imaging studies. Examples of such include a new lump in the breast or underarm; changes in the skin appearance of your breast, or a bloody nipple discharge.

Ask your doctor about factors that affect your risk and lifestyle changes or other steps that can lower your risk.

Talk with your relatives about your family history of cancer and speak with your doctor or a genetic counselor about referral for genetic testing.

Ask your healthcare professional about recommended screening and prevention options based on your age and risk for breast cancer. If you do not have health insurance or your health plan doesn’t cover the recommended screenings, explore national and local programs that provide access to low-cost or breast screening MRIs.

If you have been diagnosed with breast cancer, it’s important to make sure that you are offered guideline-recommended care given your and type of cancer. Obtain a copy of your medical records and consider getting a second opinion on your diagnosis and treatment plan. Ask your doctor about treatment clinical trials for which you may be eligible.

Share your thoughts on this XRAY review by taking our brief survey.

posted 8/5/21

Reference

American Cancer Association of Cancer Research, AACR Cancer Disparities Progress Report 2020.

Photo by Eye for Ebony on Unsplash.

- When should I begin routine screening for breast cancer?

- How often should I have routine screening for breast cancer?

- Given my family history of breast cancer, do you recommend genetic counseling and testing?

- What factors put me at risk for breast cancer?

- What factors can I change that would lower my breast cancer risk?

- What is the best treatment option for my breast cancer?

- What factors put me at risk for poor treatment outcomes?

- Am I a good candidate for any clinical trials involving breast cancer treatment?

The following clinical research studies focus on addressing in cancer:

- NCT04854304: Abbreviate or FAST Breast for Supplemental Breast Cancer Screening for Black Women at Average Risk and Dense Breasts. This study looks at how effectively a FAST breast can successfully detect breast cancer in Black women with dense breasts.

- PREVAIL Study: A Genetic Education and Genetic Testing Study for African American Men with Cancer or with a Strong Family History of Cancer. PREVAIL is a patient-choice study where African American men with cancer or with a strong family history of cancer can choose to either view a pretest genetic education video before having genetic testing or meet with a genetic counselor before genetic testing.

- Exploring the Experience of Asian Patients Receiving Results from Cancer Genetic Testing. This study aims to understand the experience of Asian patients at least 18 years of age who received genetic test results within the past two years.

- Social Support and Coping Strategies Among LGBTQIA+ Cancer Patients.This study explores how different levels of support systems influence coping strategies among LGBTQIA+ cancer patients.

- Understanding the Needs of LGBTQIA+ Caregivers Supporting People with Cancer. This study team wants to understand the experiences of LGBTQIA+ caregivers supporting people with cancer, and what interventions or services could fill their needs and support their health.

-

Learning about the Needs of Autistic People Related to Breast Cancer Screening and Testing. The goal of this study is to learn about people’s needs for information, support and services related to breast health, breast cancer risk and screening. The information will be collected through an online survey.

Updated: 09/29/2025

Who covered this study?

U.S. News & World Report

Cancer health disparities continue

This article rates 4.0 out of

5 stars

This article rates 4.0 out of

5 stars

Yahoo! News

AACR report on cancer disparities reveals harsh truths and a call to action

This article rates 4.0 out of

5 stars

This article rates 4.0 out of

5 stars

Cancer Health

AACR releases first cancer disparities progress report

This article rates 3.0 out of

5 stars

This article rates 3.0 out of

5 stars