Update: Cancer disparities: Colorectal cancer in African Americans

The American Association for Cancer Research (AACR) released a 2020 report about cancer disparities among racial and ethnic groups in the United States. In this XRAY review, we highlight data from the report about the burden of colorectal cancer in African Americans, who have the highest rates of diagnosis and death related to the disease among all racial and ethnic groups. (Posted 4/27/21)

Este artículo está disponible en español.

Contents

| At a glance | Clinical trials |

| Update findings | Guidelines |

| Context | Questions for your doctor |

| What does this mean for me? | Resources |

UPDATE AT A GLANCE

What is this update about?

This report is about disparities in colorectal cancer rates, related deaths, and cancer screening in African Americans, as well as factors that may contribute to the disease in this population.

Why is this update important?

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most common cancer diagnosed in African American adults. About 20,000 new cases were diagnosed in this population in 2019.

Rates for colorectal cancer diagnosis and death among African Americans declined over the past decade. Still, these rates are higher than rates among people of other races or ethnicities. The AACR updated the status of colorectal cancer in African Americans and disparities of the disease compared with other racial or ethnic groups. The update highlighted risk factors, screening, rates of diagnosis, treatment and deaths related to colorectal cancer among African Americans.

Update findings

The AACR Cancer Disparities Progress Report 2020 included the most recent research of colorectal cancer involving African Americans. The following topics and research findings were included in the report.

Screening of colorectal cancer in African Americans

- Almost 20 percent of the disparity in colorectal cancer mortality rate between African Americans and white Americans is attributed to lower rates of screening among African Americans.

- African Americans aged 50 and older are most likely to undergo screening for colorectal cancer of any non-white racial or ethnic group.

- Factors that keep African Americans from being screened include:

- Lack of awareness about colorectal cancer

- Being unaware of the benefits of screening

- Fear of a colonoscopy, fear of pain and financial concerns

- Lack of insurance and access to care, and

- Not receiving a health care provider’s recommendation to have screening

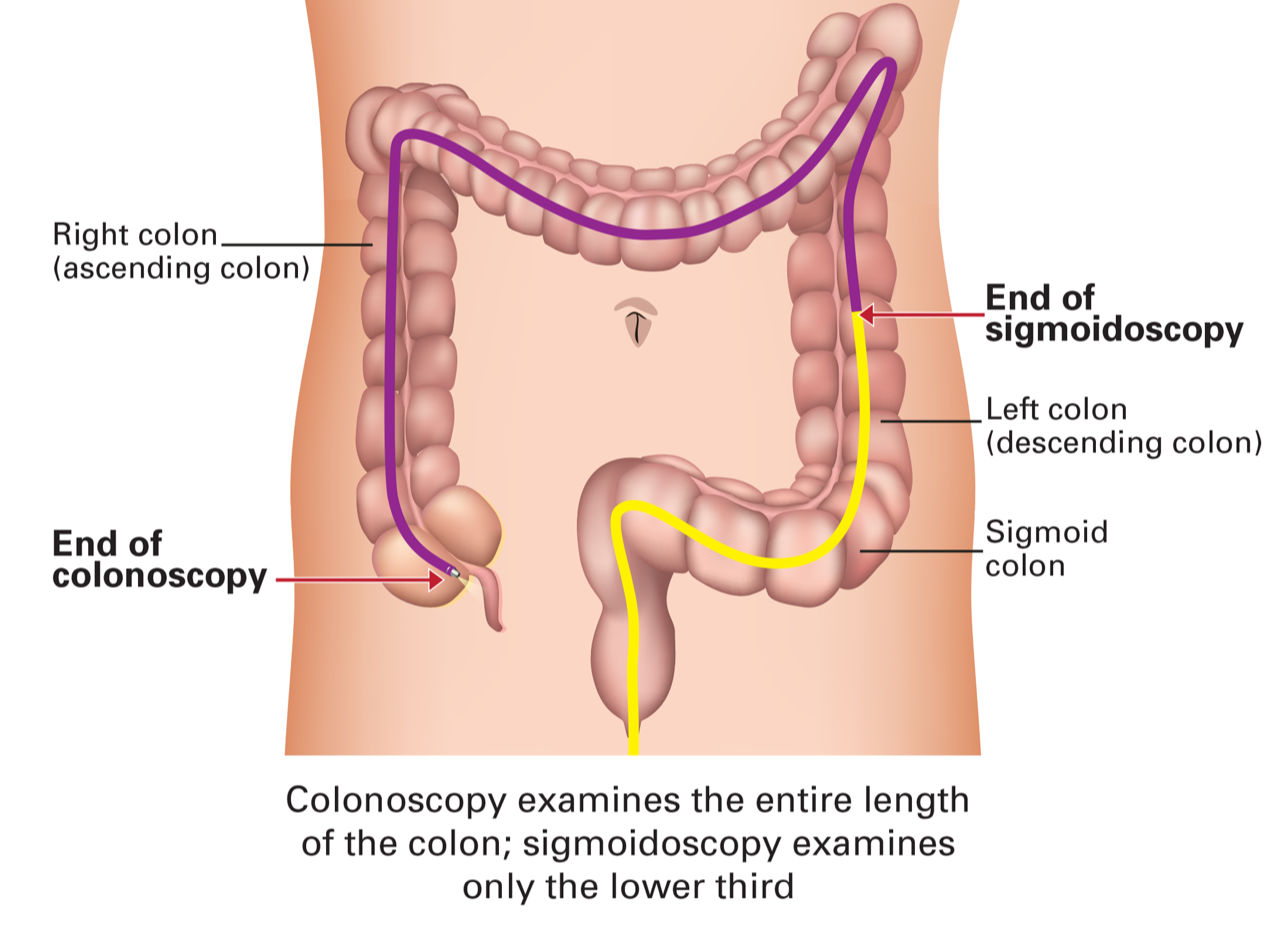

- African Americans have a high prevalence of cancer on the right side of the colon, which includes the cecum, ascending colon and proximal transverse colon. These organs cannot be reached by flexible sigmoidoscopy screenings but can be reached by colonoscopy. (See the variety of colorectal cancer screening tests in Guidelines.)

- Among African Americans with an identified gene alteration in genes linke to colorectal cancer risk, more are variants of uncertain significance are detected (where it is not clear if the mutation will increase disease risk or not) than among whites. This may reflect lack of focus or followup research on these genetic mutations.

Rates of colorectal cancer in African Americans

- Approximately 20,000 new diagnoses of colorectal cancer occur annually in African Americans adults aged 18 and older.

- African American men are 26 percent more likely to be diagnosed than African American women.

- Rates of colorectal cancer decreased by roughly 3 percent per year in African Americans from 2005 to 2016.

Disparities between African Americans and white Americans

- The overall rate of colorectal cancer is nearly 20 percent higher in African Americans.

- The incidence of colorectal cancer before age 50 is twice as high in African Americans. The recent deaths of Chadwick Boseman at age 43 and Natalie Desselle-Reid at age of 53 serve as tragic examples of the disproportionate impact of early-onset CRC among the African American community.

- Some early case of CRC may be due to hereditary forms of CRC including mutations in genes. On average, the rate of mutations (which increases risk of colorectal cancer) in African Americans is similar to white Americans. However, mutations may be more frequent among those with particular ancestries (e.g., people from Zimbabwe).

- African Americans are more than four times likely to be diagnosed with proximal (right-sided) colon cancer, which is more aggressive than left-sided colon cancer.

Disparities between African Americans and all other racial and ethnic groups

- Compared with all racial/ethnic groups, African Americans are more likely to receive an initial diagnosis of colorectal cancer when the disease is more advanced and harder to treat.

Treatment disparities in African Americans compared with non-Hispanic white Americans

- African Americans are less likely to be recommended the right care for the type and of their cancer. As a result, they are less likely to receive surgical treatments, radiation and chemotherapy, which may greatly benefit their health and survival.

- African Americans are less likely to participate in clinical trials for cancer treatment that may include access to new and beneficial therapies.

- The following barriers are more likely to prevent African Americans from receiving colorectal cancer treatment:

- Lack of health insurance coverage

- Cost of services

- Transportation difficulties

- Lack of knowledge about colorectal cancer

Deaths due to colorectal cancer in African Americans

- African Americans are most likely to die from colorectal cancer compared to individuals of any other race or ethnicity.

- Each year an estimated 2,300 African American adults will die from colorectal cancer.

- Only 60 percent of African Americans with colorectal cancer will live at least five years after diagnosis, compared with 66 percent of their white counterparts and 68 percent of their Asian American or Pacific Islander counterparts.

Factors that increase colorectal cancer risk for African Americans and contribute to

- Smoking

- Although African Americans and white Americans have similar rates of smoking, African Americans are three times more likely to smoke menthol cigarettes. According to the , menthol, which is used to mask the harsh taste of tobacco, likely poses a greater public health risk than nonmenthol cigarettes.

- African American adults and children are two times more likely to be exposed to secondhand smoke than any racial or ethnic group.

- Weight

- African American adults (75 percent) are more likely to be overweight or obese than non-Hispanic white Americans (70 percent).

- Diet

- Although the quality of the African American diet has improved, research shows that they report a lower intake of whole grains, fruits, and vegetables than any other racial or ethnic group.

- Physical Activity

- African Americans (35 percent) are more likely to report no leisure-time physical activity than non-Hispanic white Americans.

- Social and Economic Factors

- Currently, 21 percent of African Americans live below the federal poverty level, compared with 8 percent for non-Hispanic white Americans. The incidence of colorectal cancer is 35 percent higher among African American men living in the poorest US counties than those living in the most affluent counties.

- African Americans are twice as likely as white Americans to be uninsured. Individuals who lack health insurance have a higher risk of poor outcomes from cancer compared with those who are insured.

- Systemic racial discrimination has been shown to contribute to poor physical and mental health among minorities and has been linked to increased cancer risk among African Americans.

- Environmental Factors

- African Americans and Hispanic Americans are more likely than any other race or ethnicity to be exposed to higher levels of pesticides and other household chemicals that have been linked to the development of colorectal cancer.

- African Americans are more likely than non-Hispanic white Americans to be exposed to higher levels of outdoor air pollution, which is a known cancer-causing agent.

Context

Cancer disparities based on race and ethnicity are the results of many factors. Some disparities are due to factors that can be modified, such as smoking, while others may be due to the long history of racism in our society. This has resulted in unfavorable outcomes for African Americans and other historically marginalized racial and ethnic groups. These unfavorable outcomes include high poverty rates, lack of access to healthy foods and racial bias within our healthcare system—all of which can result in worse health and treatment outcomes.

What does this mean for me?

If you are African American, be aware that your risk of colorectal cancer may be higher than other people’s risk. Ask your doctor about factors that affect your risk and whether making any lifestyle changes or other steps can lower your risk. You may want to ask your doctor what your risk is given your personal or family history and what screenings are recommended. Under the Affordable Care Act, insurance companies are required to pay for colorectal cancer screening—in many cases with no out-of-pocket expenses—for people between the ages of 50 and 75.

Importantly, of all the screenings available, colonoscopy can prevent many cases of colorectal cancer by finding and removing abnormalities before they can become cancer. Although sigmoidoscopy can also find and remove , this procedure uses a shorter scope that doesn’t examine the entire colon. It misses the more aggressive cancers that may develop in the right colon (first part of the colon). Speak with your doctor to decide which screening test is best for you.

Aspirin has also been shown to lower the risk for colorectal cancer, as well as heart disease. FORCE reviewed this in a recent XRAY review linked here. Ask your doctor if you might benefit from daily low-dose aspirin to lower your risk for both diseases.

If you have been diagnosed with cancer, it’s important to make sure that you are offered guideline-recommended care given your and type of cancer. Obtain a copy of your medical records and get a second opinion on your diagnosis and treatment plan.

Share your thoughts on this XRAY article by taking our brief survey.

posted 4/27/21

References

American Cancer Association of Cancer Research, AACR Cancer Disparities Progress Report 2020.

Siegel R, Miller K, Goding Sauer A, et al. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020; 70(3):145-164. March 5, 2020. doi:10.3322/caac.21601

Disclosure

FORCE receives funding from industry sponsors, including companies that manufacture cancer drugs, tests and devices. All XRAYS articles are written independently of any sponsor and are reviewed by members of our Scientific Advisory Board prior to publication to assure scientific integrity.

The U.S. government and many health organizations have recommendations for colorectal cancer screening and other preventative measures. Recommendations from the American Cancer Society (ACS), the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) and the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force () are shown below.

Screening Recommendations

|

|

ACS |

NCCN |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

Begin routine colorectal cancer screening for people at average risk |

Age 45 |

Age 45 |

Ages 45-49 Age 50 |

|

Discontinue routine screening for those at average risk |

Age 75 |

Age 75 |

Age 75 |

|

Screen adults ages 76-85 based on patient preferences, health status and prior screening history |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes (Grade C) |

|

Advise against colorectal cancer screening beyond 85 years of age |

Yes |

- |

- |

|

Begin routine colorectal cancer screening for people at high risk* |

Before age 45: specific age depends on risk factor |

Before age 45: specific age depends on risk factor |

- |

*Includes people with any of the following: a personal history of colorectal cancer or certain types of polyps; family history of colorectal cancer; personal history of inflammatory bowel disease; or a confirmed or suspected hereditary colorectal cancer syndrome, such as familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) or .

For people with , gene-specific recommendations vary for frequency and age to start screening for colorectal cancer (see this link for more information).

Colorectal cancer screening tests

Stool‐based tests are performed on a stool (feces) sample to help diagnose conditions affecting the digestive tract, including colorectal cancer. Like most screening diagnostics, the frequency of stool tests varies. Stool tests include:

|

Stool Test |

Recommended frequency |

|

Fecal protein test (FIT) |

Once per year |

|

Fecal blood test (gFOBT) |

Once per year |

|

Fecal test (FIT-DNA) |

Once every 1-3 years |

Structural (visual) examinations look inside the colon and rectum for areas that might be cancerous or have . These include:

|

Structural examinations |

Recommended frequency |

|

Colonoscopy |

Once per 10 years |

|

CT colonography |

Once per 5 years |

|

Flexible sigmoidoscopy |

Once per 5 years |

|

Flexible sigmoidoscopy with FIT |

Flexible Sigmoidoscopy every 10 years plus FIT every year |

Colonoscopy prevents many cases of colorectal cancer by finding and removing abnormalities before they become cancer. Although sigmoidoscopy can also detect and remove , this procedure uses a shorter scope that doesn’t examine the entire colon.

For people at high risk of colorectal cancer, colonoscopy is recommended for cancer screening.

Insurance coverage for screening

Colorectal cancer screenings such as stool-based tests (see descriptions above) beginning at age 45 have been graded "A" or "B" by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (). This means that these services effectively detect or prevent the disease.

- The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) requires that most health plans cover 100% of one colorectal cancer screening at its recommended frequency (see colorectal cancer screening tests table below) with no out-of-pocket costs to patients age 45 and older—no matter their risk.

- Medicare beneficiaries—regardless of their age—are allowed one colonoscopy covered at 100% every 6 years for those at average risk and one colonoscopy per 24 months for those at high risk.

- Medicaid coverage of colorectal cancer screening varies by state. Individuals who qualify based on their state’s decision to expand Medicaid under the ACA are entitled to the same screening and preventive services as those who are covered by private insurance.

For individuals with increased risk, certain states require insurance coverage for colonoscopy beyond the requirements of the ACA. Check with your state insurance commission to determine if you live in one of these states.

Updated: 04/08/2025

- When should I begin routine screening for colorectal cancer?

- What factors put me at risk for colorectal cancer?

- What is the best treatment option for my colorectal cancer?

- What factors put me at risk for poor treatment outcomes?

- Would I be a good candidate for any clinical trials involving colorectal cancer treatment?

The following studies look at colorectal cancer screening or prevention:

- NCT03218423: Longitudinal Performance of Epi proColon (PERT). This study evaluates a blood test for colorectal cancer.

- NCT04940442: Outreach and Choice in Colorectal Cancer Screening. This study compares participation in colorectal cancer (CRC) screening by fecal immunochemical test [FIT] and colonoscopy.

Other colorectal cancer screening and prevention studies may be found here.

Updated: 01/13/2025

The following clinical research studies focus on addressing in cancer:

- NCT04854304: Abbreviate or FAST Breast for Supplemental Breast Cancer Screening for Black Women at Average Risk and Dense Breasts. This study looks at how effectively a FAST breast can successfully detect breast cancer in Black women with dense breasts.

- PREVAIL Study: A Genetic Education and Genetic Testing Study for African American Men with Cancer or with a Strong Family History of Cancer. PREVAIL is a patient-choice study where African American men with cancer or with a strong family history of cancer can choose to either view a pretest genetic education video before having genetic testing or meet with a genetic counselor before genetic testing.

- Exploring the Experience of Asian Patients Receiving Results from Cancer Genetic Testing. This study aims to understand the experience of Asian patients at least 18 years of age who received genetic test results within the past two years.

- Social Support and Coping Strategies Among LGBTQIA+ Cancer Patients.This study explores how different levels of support systems influence coping strategies among LGBTQIA+ cancer patients.

- Understanding the Needs of LGBTQIA+ Caregivers Supporting People with Cancer. This study team wants to understand the experiences of LGBTQIA+ caregivers supporting people with cancer, and what interventions or services could fill their needs and support their health.

-

Learning about the Needs of Autistic People Related to Breast Cancer Screening and Testing. The goal of this study is to learn about people’s needs for information, support and services related to breast health, breast cancer risk and screening. The information will be collected through an online survey.

Updated: 09/29/2025

Who covered this study?

US News & World Report

Cancer Health Disparities Continue

This article rates 4.0 out of

5 stars

This article rates 4.0 out of

5 stars

City Of Hope

AACR report on cancer disparities reveals harsh truths and a call to action

This article rates 4.0 out of

5 stars

This article rates 4.0 out of

5 stars

Cancer Health

AACR Releases First Cancer Disparities Progress Report

This article rates 3.0 out of

5 stars

This article rates 3.0 out of

5 stars