Study: Racial disparities in BRCA testing: Why?

Contents

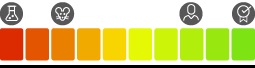

| At a glance | In-depth |

| Findings | Limitations |

| Guidelines | Resources |

| Questions for your doctor |

STUDY AT A GLANCE

This study is about:

Uncovering the reasons why black women are less likely to receive testing than white women.

Why is this study important?

Black women have a similar, if not higher chance of carrying a mutation than non-Jewish white women. Yet studies show that fewer black women have testing. Researchers do not understand why this disparity exists.

Study findings:

- Black women with breast cancer were less likely than white women to have testing.

- About one-quarter of black women had testing, compared to almost one-half of white women.

- Black women with breast cancer were less likely to report positive attitudes about testing and were more likely to report negative attitudes.

- The care of black and white women with breast cancer is highly segregated across surgeons and oncologists.

- Oncologists and surgeons who cared for most black patients were younger and more likely to be female.

- A physician recommendation was strongly associated with testing. For unknown reasons, surgeons and oncologists were about 1.5 times less likely to recommend testing to their black patients than their white patients.

- Surgeons and oncologists who took care of more black patients did not differ in their attitude towards testing compared to surgeons and oncologists who saw more white patients.

- Characteristics (age, sex, U.S.-trained, employment type, and when they graduated from medical school) of surgeons and oncologists did not explain the racial disparity in testing recommendation between black and white women.

What does this mean for me?

This study suggests that that black women are less likely to get testing, possibly because their health care providers are less likely to recommend it, even though black women are as likely (if not more likely) to carry a mutation than white non-Jewish women. Health care providers should work to ensure that they communicate genetic service recommendations to all high-risk women, regardless of their race. Black women who are concerned about breast cancer in their families should ask their health care providers if genetic counseling or genetic testing is appropriate for them.

Posted July 21, 2016

Share your thoughts on this XRAYS article by taking our brief survey.

This article is relevant for:

African American women who have been diagnosed with breast cancer

This article is also relevant for:

people with breast cancer

people with ER/PR + cancer

people with Her2-positive cancer

people with metastatic or advanced cancer

people with triple negative breast cancer

Be part of XRAY:

IN DEPTH REVIEW OF RESEARCH

Study background:

Black and White non-Jewish/non-Hispanic women have similar chances of carrying a mutation. A recent study suggests that young black women with breast cancer are about twice as likely to carry a mutation compared to non-Hispanic white women. However, many studies have shown that black women do not get tested for as often as white women do. Researchers do not understand why this racial disparity exists.

When researchers of this study explored a possible explanation for this disparity, they noted that racial groups could be segregated unevenly in U.S. cities, suggesting that black women and white women may not be seeing the same healthcare providers. Anne Marie McCarthy and her colleagues at Harvard Medical School and other institutions published research in the Journal of Clinical Oncology to determine if black and white women are seeing different types health care providers and whether or not this accounts for the racial disparity in testing.

Researchers of this study wanted to know:

Why are black women not receiving testing as often as white women?

Population(s) looked at in the study:

The women in this study were between 18-64 years old, from Florida and Pennsylvania, and were diagnosed with localized or invasive breast cancer between 2007-2009. A total of 3,016 women (69% white and 31% black) were surveyed, with a response rate of 61%. Physicians were also surveyed; their response rate was 29% (808 oncologists and 732 surgeons).

Study findings:

- The care of black and white women with breast cancer is highly segregated across surgeons and oncologists.

- Oncologists and surgeons who cared for the most black patients were younger and more likely to be female.

- A physician recommendation was strongly associated with testing. For unknown reasons, surgeons and oncologists were about 1.5 times less likely to recommend testing to their black patients than their white patients.

- Surgeons and oncologists who cared for more black patients did not differ in their attitude towards testing compared to surgeons and oncologists who saw more white patients.

- The characteristics of the surgeons and oncologists (age, sex, U.S.-trained, employment type, and when they graduated from medical school) did not explain the racial disparity in testing recommendations between black and white women.

- Black women with breast cancer were less likely than white women to have testing.

- About one-quarter of black women had testing compared to almost one-half of white women.

Limitations:

While 61% of women who qualified for the study responded to the survey, the characteristics of the respondents, including age, race and year of diagnosis, differed from the women who did not respond. Black women were also less likely than white women to provide data about their physicians. Because this data was based on a survey, some bias could exist in the women’s answers. For example, women who were tested may have been more likely to remember that their physician recommended testing than women who chose not to undergo testing.

This was a population-based study, meaning that not all the women involved met guidelines for genetic testing—the results might be different if study participants included only women who met guidelines for genetic testing. Additionally, researchers could not compare women who received care at academic centers versus non-academic centers. This study only looked at oncologists and surgeons. Other types of doctors could be involved, although in the researchers’ experience, few patients receive breast cancer care from health care providers other than oncologists and surgeons.

Finally, this study included only women from Florida and Pennsylvania. The researchers state that while those populations are large and diverse, it is possible that the patterns in those states are not the same as what may be seen in other areas in the U.S.

Conclusions:

This study suggests that although black and white women do not see the same health care providers (some providers see more black women than white and vice versa because of the area in which they practice), that does not explain why black women have testing less often than white women. This study did reaffirm that fewer black women are receiving recommendations to get testing than white women. The researchers suggest this may be because family cancer history information may be less complete among black women. This could stem from either less awareness of cancer diagnoses in other family members, or healthcare providers not asking about family history as often for black women as they do for white women. Even though black women have a similar, if not higher chance of carrying a as a non-Jewish white women, when researchers applied the 2007 risk assessment guidelines to their study population, they found that a lower proportion of black women were classified as “high risk” compared to white women. Using the current criteria, which includes women diagnosed with breast cancer before age 45 (previous guidelines included patients before age 40) and women with before age 60, might increase the number of black women who would meet national guidelines for testing.

Because the study did not include discussion about genetic counseling, it is unknown whether these patients saw genetic counselors, and whether seeing a genetic counselor increased genetic testing.

Ultimately, more work needs to be done to understand why this racial disparity in testing between black and white women exists. Until then, healthcare providers should be more conscious to fully assess risk for black women, who should question their health care providers if they believe they may be at genetic risk for breast cancer.

Posted July 21, 2016

Share your thoughts on this XRAYS article by taking our brief survey.

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network has guidelines on who should undergo genetic counseling and testing. If you have been diagnosed with breast cancer, you should speak with a genetics expert about genetic testing if any of the following apply to you:

- You have a blood relative who has tested positive for an

- You have any of the following:

- Breast cancer at age 50 or younger

- Male breast cancer at any age

- Ovarian cancer at any age

- at any age

- Two separate breast cancer diagnoses

- Eastern European Jewish ancestry and breast cancer at any age

- Lobular breast cancer and a family history of diffuse gastric cancer

- For treatment decisions for people with breast cancer or people with early , breast cancer who are at high-risk for recurrence

- Testing of your tumor shows a mutation in a gene that is associated with

OR

- You have one or more close family members who have had:

- Young-onset or rare cancers

- Breast cancer at age 50 or younger

- Male breast cancer, ovarian cancer, pancreatic cancer, or cancer at any age

- Two separate cancer diagnoses

- prostate cancer or cancer that is high-risk or very-high-risk group.

The American Society of Breast Cancer Surgeons (ASBrS) released guidelines in 2019 that recommend all women diagnosed with breast cancer have access to genetic testing for inherited mutations in breast cancer genes.

If you are uncertain whether you meet the guidelines above and you are interested in or considering genetic testing, you should speak with a cancer genetics expert.

Updated: 07/28/2023

- I had breast cancer before the age of 50; should I consider genetic counseling or testing?

- My (sister/mom/grandma) got breast cancer at an early age, but I do not know much about my family history. Should I get consider genetic counseling and/or genetic testing?

- Some of the women on my dad’s side of the family had breast cancer before age 45. Does this affect me?

- Will my insurance cover genetic testing?

- If my insurance won't cover genetic testing and I still would like to have it, are there low-cost options for testing?

- Can you refer me to a genetic counselor?

The following clinical trials include genetic counseling and testing.

- NCT02620852: WISDOM Study: Women Informed to Screen Depending on Measures of Risk offers women ages 40-74 the opportunity to undergo risk assessment and genetic testing in order to determine the best breast screening options based on their situation.

- NCT05562778: Chatbot to maximize genetic risk assessment. Researchers are testing whether a mobile health platform, known as a "chatbot" can improve rates of genetic testing among Medicaid patients with an elevated risk having an .

- NCT05427240: eHealth Delivery Alternative for Cancer Genetic Testing for (eReach2). This study will look at the effectiveness of offering web-based options for pre/post-test genetic counseling to provide equal or improved timely uptake of genetic services and testing.

- NCT05694559: Connecting Black Families in Houston, Texas to Genetic Counseling, Genetic Testing, and Cascade Testing by Using a Simple Genetic Risk Screening Tool and Telegenetics. This study will provide genetic testing to 150 Black individuals and families and provide genetic counseling and risk reduction resources to individuals with a mutation linked to increased cancer risk.

Other genetic counseling or testing studies may be found here.

Updated: 02/29/2024

The following clinical research studies focus on addressing in cancer.

- NCT04336397: Stool to Improve Colorectal Cancer Screening Among Alaska Native People. The goal is to determine the acceptability of a stool test to detect colorectal cancer within the Alaska tribal healthcare system.

- NCT04476654: Improving Uptake of Genetic Cancer Risk Assessment in African American Women-Video. This study looks at the usefulness of intervention with a culturally-tailored video to improve uptake of genetic counseling in Black women who are at increased risk of .

- NCT04450264: Increasing African Immigrant Women's Participation in Breast Cancer Screening (AIBCS). The study will look at barriers and facilitators to breast cancer screening among African-born immigrants, and adapt and test the Witness Project breast cancer education program to address breast screening disparities in this population.

- NCT04854304: Abbreviate or FAST Breast for Supplemental Breast Cancer Screening for Black Women at Average Risk and Dense Breasts. This study is looking at how effectively a FAST breast can successfully detect breast cancer in Black women with dense breasts.

- NCT03640208: Educate, Assess Risk and Overcoming Barriers to Colorectal Screening Among African Americans. This research will study a community-based intervention to educate and overcome barriers to screening among African Americans who are 45 years or older with no personal or family history of colorectal cancer or inflammatory bowel disease.

- NCT04392050: A Community-Based Educational Intervention to Improve Colorectal Cancer Screening. This study will look at what makes it easy or difficult for underserved populations to have colorectal cancer screenings, with a focus on African American, Latinx and Asian people.

- NCT03550885: Diet Modulation of Bacterial Sulfur and Bile Acid Metabolism and Colon Cancer Risk. This effort will look at how bile secretion into the intestine selects for bacteria that produce tumor-promoting molecules in African Americans with an increased risk for colorectal cancer.

Updated: 11/03/2022

The following organizations offer peer support services for people with, or at high risk for breast cancer:

- FORCE peer support:

- Our Message Boards allow people to connect with others who share their situation. Once you register, you can post on the Diagnosed With Cancer board to connect with other people who have been diagnosed.

- Our Peer Navigation Program will match you with a volunteer who shares your mutation and situation.

- Connect online with our Private Facebook Group.

- Join our virtual and in-person support meetings.

- Other organizations that offer breast cancer support:

Updated: 11/29/2022

The following resources can help you locate a genetics expert near you or via telehealth.

Finding genetics experts

- The National Society of Genetic Counselors website has a search tool for finding a genetic counselor by specialty and location or via telehealth.

- InformedDNA is a network of board-certified genetic counselors providing this service by telephone. They can also help you find a qualified expert in your area for face-to-face genetic counseling if that is your preference.

- Gene-Screen is a third-party genetic counseling group that can help educate, support and order testing for patients and their families.

- JScreen is a national program from Emory University that provides low-cost at-home genetic counseling and testing with financial assistance available.

- Grey Genetics provides access to genetic counselors who offer genetic counseling by telephone.

- The Genetic Support Foundation offers genetic counseling with board-certified genetic counselors.

Related experts

Genetics clinics

- The American College of Medical Genetics website has a tool to find genetics clinics by location and specialty.

Other ways to find experts

- Register for the FORCE Message Boards and post on the Find a Specialist board to connect with other people who share your situation.

- The National Cancer Institute (NCI)-designated comprehensive cancer centers have genetic counselors who specialize in cancer.

- FORCE's toll-free helpline (866-288-RISK, ext. 704) will connect you with a volunteer board-certified genetic counselor who can help you find a genetics expert near you.

Updated: 07/21/2023

Who covered this study?

Breastcancer.org

Black women less likely to have genetic testing than white women, but not because they see different doctors

This article rates 4.0 out of 5 stars

This article rates 4.0 out of 5 stars

Oncology Nurse Advisor

BRCA1/2 testing recommendations vary between black and white patients

This article rates 3.0 out of 5 stars

This article rates 3.0 out of 5 stars